博文

海上方舟:一个犹太女孩在上海的故事

热度 27 |||

白露为霜注:大女儿大宝自小热爱历史,高中有段时间对二战史,特别是大屠杀 (Holocaust)

的历史很有兴趣,做了很多研究。上海犹太人是其中短暂但令人印象深刻的事件,她花了很多时间找到了一位幸存者,并进行了采访。本文后来在一家英文报纸上发表。随着时间推移和亲历这段历史的人的渐渐凋零,文章的文献价值慢慢显露出来。白露特意把它翻译成中文,希望有更多的人了解这一段既是犹太人又是中国人的历史。博文中使用的部分照片来自于中国摄影家协会会员郭大公先生(网名:gdecn),特此鸣谢。

海上方舟:一个犹太女孩在上海的故事

(Eva Hirschel’s Shanghai Story)

我轻敲房门,随后听见了她的声音,“门是开的。”

这是一间位于美国北加州的两居室公寓,伊娃·赫歇尔 (Eva Hirschel) 是一个小个的老太太,坐在墙角的窗边,看着孩子们在院子里嬉闹。

我称她为伊娃,虽然她可以做我的外婆了。我放置停当录音机,不需要做任何提示,她侃侃而谈,伊娃已经准备好讲她的故事。

1933年希特勒成为德国总理(Chancellor)。在此前5年,伊娃出生于德国布雷斯劳 (Breslau)的一个犹太家庭。他们是普通人,带着恐惧,敬畏和难以置信的混合心情看着一个疯子爬上权利之颠。作为一个孩子,她见证了“水晶之夜”(Kristallnacht) [注1] 的疯狂的仇恨和令人心碎的残酷。弟弟在学校被打,她被希特勒青年团(Hitler Youth)羞辱和吐唾沫。

1940年她11岁时,父亲被关在布痕瓦尔德集中营(Buchenwald )六个星期。当他被放出来后一家人感觉到德国是不能待了,伊娃和父母,还有弟弟在意大利热那亚(Genoa)搭上了去上海的轮船。

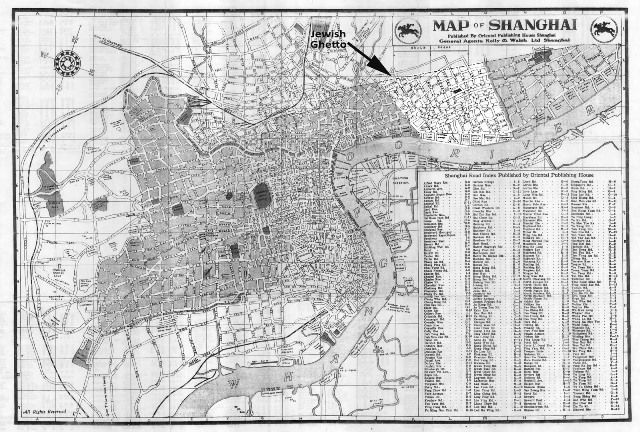

中国上海,一个由中国和国际两个市政局共同管理的开放港口城市,不需要入境签证,是世界上唯一愿意接受他们的地方。伊娃后来发现,她们乘坐的意大利客轮,Conte Verde,是最后一班离开欧洲的客轮。在半途中意大利加入第二次世界大战,她家族其余的人都被困欧洲了。

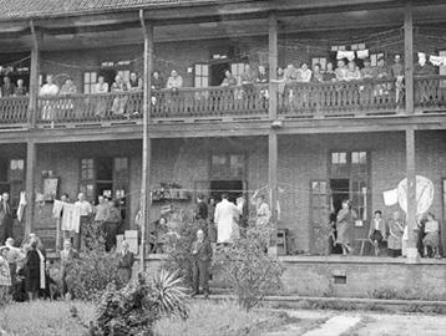

在30年代末和40年代初,对于超过两万欧洲犹太人来说上海曾经是家。这意味着绝望的生活条件,无时不在的饥饿,奇怪的语言;这意味着穿越数千公里的不确定海洋,到达罪犯黑帮出没,混乱习以为常的城市。但最重要的是,当纳粹党旗飘扬在从巴黎到波罗的海的欧洲大地时,上海意味着一个躲避希特勒和大屠杀的避风港。

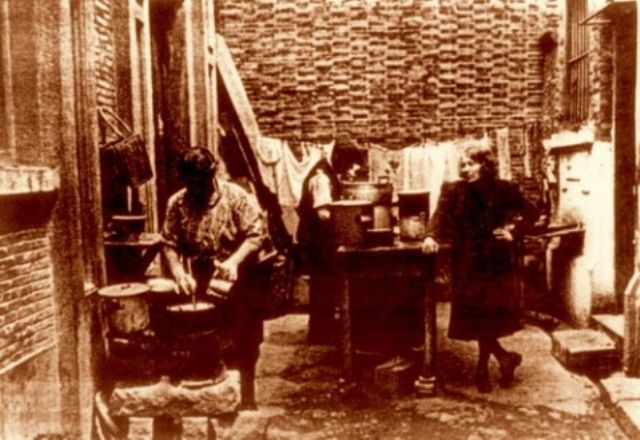

在局促困顿和疾病缠身之中,伊娃在上海度过了她的少年时期。当时上海被日军占领,日本占领者会因为最轻微的事情就拿刺刀乱刺中国人。到了1943年[注2],犹太人被赶进贫困的“虹口隔离区”( Hongkew Ghetto)。早上,死于饥饿或疾病,被报纸包裹的尸体就会出现在街道上。

伊娃15岁时退学来支持她的家庭,母亲体弱多病,父亲是个酒鬼,弟弟还只是个孩子,她便成了家庭的主心骨。她回忆说,“家人同另外24人住在一所房子,共用一个只有冷水的浴缸和两个小厕所。他们住在一个房间里中间隔一个夹板墙,另外半间住另一对夫妇。”

然而并非所有上海的回忆都是暗淡的。伊娃,如同30年代世界各地数百万记的儿童,崇拜偶像秀兰·邓波儿(Shirley Temple)。她一直以为美国童星也跟自己一样 – 是一个德国犹太裔女孩。

伊娃回忆到: “我刚到上海只有几个星期,有一天走在一条岔路上,我正巧路过一家电影院,在那里有一张大型的海报,让我惊喜万分的是秀兰·邓波儿正对着我微笑。我几乎要拥抱了她,我真的很高兴而且松了口气。“

伊娃跑回家,告诉母亲这个好消息。

“秀兰,秀兰·邓波儿。是不是很美妙?她离开了德国。她安全了,而且生活在上海。我知道。我看到了她的照片了。“

数以千记的犹太人也像伊娃那样在上海活了下来 – 靠着决心,智谋,和百折不挠的精神,使他们能够战胜来到新城市的诸多挑战。很短时间内,一个繁荣,热闹非凡的犹太文化便在上海出现 。一流的剧院,芭蕾,音乐会,报纸被印成十几种语言,还组成了校际运动队。上海的犹太区被称为“小维也纳”。

由于日本人的新闻审查,上海的犹太人完全不知道他们在欧洲的家人怎么样了。直到战争结束后,艾森豪威尔视察解放了的纳粹集中营的图像传来,他们才知道这一恐怖的消息。

“谁能想象得到吗?我们的隔离区里一片死寂,你可以听到针掉在地上。没有一个人没有失去亲友的。 发生在1940年呢?发生在德国?发生在歌德,尼采,勃拉姆斯和贝多芬的国家?我永远无法理解这一切。”

伊娃留在欧洲家族的成员都死于大屠杀,如果不是在身体上,便是在心灵上。在20世纪70年代,她远赴柏林看望家族唯一的幸存者,曾在集中营中待过的小姨。“我的阿姨,我还是一个小女孩的时候就知道她,我总是到他们家度过假期。她不知道我是谁,我来做什么呢?“

心碎不已,她再也没有回到欧洲去。

大多数上海犹太人在二战结束后便去了美国,加拿大,澳大利亚,以色列等地开始了新的生活。少数留下来的经历三年的中国内战(解放战争),和毛时代的早期,但到了50年代末,上海繁荣一时的犹太区已经全部消失了。

尽管困难和饥饿,伊娃认为她在上海的经历是非常积极的:“我们很快长大 - 我们学会了责任,我们学会了互相帮助。我不羡慕这里(美国)的孩子的一切。我不会拿它换世上任何的东西。“

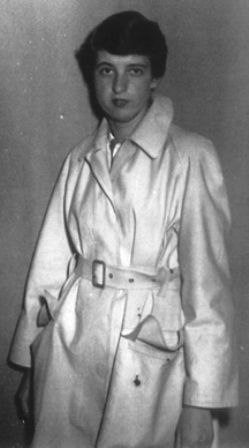

伊娃的一生是普通的,同时也是不寻常的。她拿出盖有尘土的相册,从泛黄的页面里走出一个鲜活的年轻女子,在酒吧与朋友喝酒, 坐在B-29轰炸机翼尖上,挎着身穿美军制服的新墨西哥州“甜心”的手臂咯咯地笑。她的笑容,她的举止,她的活力掩饰了内心的痛苦。

50年代的伊娃·赫歇尔

我第一次见到伊娃是在北加州Cotati的尼珥沙洛姆(Ner Shalom)犹太教堂在的一次会议上。我读过不少书,听了看了许多关于大屠杀的录音和录相。不过伊娃是我采访的第一个幸存者,尽管她拒绝承认她是一个“幸存者”。采访给我留下了一个坚定的信念,个人的沟通比任何媒体能产生的力量强大得多。作为学生,我们可以为这种沟通做出自己的贡献,这样才能确保大屠杀的确“永远不再发生” (Never Again)。

我的心里会永远带着一个影像:一个小女孩在寒冷的,裸露的意大利火车站上,不知道她是否会被允许离开和活下去。这时时提醒自己,我们生活在一个充满偏见,仇恨和暴力的世界。因此,我们的责任不仅仅是口头上说,“我们记住了”,而是每天都把这句话行出来。在缅怀那些偏见和歧视受害者的同时,我们必须学会放弃自己的偏见和仇恨的武器。

这有时看起来几乎是不可能。

然而,我问过伊娃或者其他上海犹太人有没有想过复仇。她激烈地摇头:“有忧伤,有悲痛,忧伤总是在的。但是,报复 - 没有,没有,从来没有”。

这句话永远不会停止激励我。

[注1] “水晶之夜”(也翻译成“碎玻璃之夜”)是指1938年11月9日至10日凌晨,纳粹党员与党卫队袭击德国全境的犹太人的事件。这被认为是对犹太人有组织的屠杀的开始。

[注2] 日军在八一三后占据了上海,但早期并没有进入租界,犹太人日子相对好过。太平洋战争爆发后,日本人完全占领租界并把在上海的交战国的侨民(包括很多犹太人)关了起来。从欧洲来的犹太人被当作无国籍侨民赶进虹口隔离区。

住在隔离区的犹太人

上海老地图标注犹太人隔离区

位于汾阳路的原犹太人俱乐部 (郭大公)

中国福利会上海少年宫原是犹太富商迦道理(Kadoorie)的宅第 (郭大公)

位于上海陕西路的原犹太会堂 (郭大公)

苏州河口原外白渡桥.由此通往昔日犹太人隔离区 (郭大公)

位于虹口区的舟山路是原犹太人隔离区的市场 (郭大公)

虹口区舟山路的原犹太人隔离区住宅 (郭大公)

提篮桥监狱周边地区是当年犹太人隔离区 (郭大公)

霍山路小学当年曾接待犹太儿童入学 (郭大公)

虹口区霍山公园曾是犹太人墓地之一 (郭大公)

2005年8月犹太人访问团在虹口霍山路寻访 (郭大公)

Eva Hirschel’s Shanghai Story

I knock, and I hear her voice: “the door’s open,”

It’s a two-bedroom apartment in Rohnert Park, California and she’s a little lady, sitting in the corner by the window, watching kids scream outside.

I call her Eva, though she could be my grandmother. I set the tape recorder down, and without prompting, she speaks. She is ready to tell her story.

Eva was born in Breslau, Germany to Jewish parents less than five years before Hitler became chancellor in 1933. They were ordinary people, who watched with a mixture of fear, disbelief, and awe as a madman came to power. As a child, she stood witness to the blind hatred and shattering cruelty of Kristallnacht or “the night of broken class”. Her brother was beaten up in school and she was humiliated and spit upon by the Hitler Youth.

She was eleven years old in 1940, when after her father spent six weeks in Buchenwald concentration camp, she and her parents, along with younger brother set sail for Shanghai by way of Genoa, Italy.

Shanghai, China was the only place that would take them, an open port city ruled jointly by the Chinese and an international municipal council which required no visa for entry. Eva would later discover that their Italian liner, the Conte Verde, was the last one out of Europe. Italy joined Germany in WWII midway through the voyage, and the rest of her family was trapped.

For over 20,000 European Jews in the late 1930’s and early 1940’s, Shanghai was once home. It meant desperate conditions, constant hunger, and strange languages. It meant traversing thousands of miles of uncertain ocean to reach a crime-infested, chaos-accustomed city. But most importantly, Shanghai meant a safe haven from Hitler and the Holocaust at a time when the Nazi flag flew from Paris to the Baltic.

Eva spent her teenage years in Shanghai, living in conditions that were impossibly cramped and disease-ridden. The Japanese occupiers bayoneted Chinese for the slightest infractions, and in 1943, Jews were herded into the poverty-stricken Hongkew “ghetto”, where corpses wrapped in newspapers appeared on the streets every morning, dead from starvation or diseases.

Eva quit school at fifteen to support her family: her mother was an invalid, her father a drunkard, and her brother a mere boy. She recalled that “[her] family lived in a house shared by 24 other people with one bathtub, cold water and two small toilets. [They] lived in one room, which was separated in half by a tiny plywood wall in order to accommodate another couple.”

Yet not all the memories of Shanghai were bleak. Eva, like millions of pre-teens around the world in 1930s, idolized Shirley Temple, and saw the American child star as a reflection of herself – a German Jewish girl.

“I had been in Shanghai only a few weeks when one day, walking down Wayside Road, I happened to pass a cinema and there to my utter joy and delight was a large poster from which Shirley’s eyes smiled at me. I could have hugged her. I was so happy and relieved.”

Eva ran home and told her mother about the news.

“Shirley. Shirley Temple. Isn’t that wonderful? She got out of Germany. She is safe and living right here in Shanghai. I know. I saw her picture.”

Thousands of other Jews survived much as Eva did -- with determination, resourcefulness, and a sort of relentless spirit that allowed them to prevail over the many challenges presented by the city. A thriving, boisterous Jewish culture developed with first-rate theatre, ballet and concerts. Newspapers were printed in half-a-dozen languages, and intramural sports teams were organized.

The Jewish quarter of Shanghai became known as “Little Vienna.”

The Jews of Shanghai knew nothing of what happened to their families in Europe, as all information was censored by the Japanese. It was not until after the war that images of Eisenhower inspecting the death camps came through, and they were given knowledge of the horrors that had come to pass.

“Who could have imagined? It was so quiet in our ghetto that you could have heard a pin drop. There wasn’t a single person who hadn’t lost somebody. In 1940? In Germany, the country of Goethe and Nietzsche and Brahms and Beethoven? I can never understand it.”

Every member of Eva’s extended clan left in Europe was lost to the Holocaust, if not in body, then in mind. In the 1970’s, she traveled to Berlin to see the lone survivor, her mother’s sister, who had been in concentration camp. “My aunt, who I knew since I was a little girl; I always spent my vacations with them, she didn’t know who I was. What was I doing there?”

She has never since gone back to Europe.

After the end of the WWII, most Jews looked towards new lives in the United States, Canada, Australia, and Israel. A few stayed behind to weather three more years of Chinese civil war, and the early days of Mao. But by the late 1950s, the once thriving Jewish ghetto in Shanghai had all but vanished.

Despite the hardship and the starvation, Eva thinks of her experiences in Shanghai as overwhelmingly positive: “We grew up so fast -- we learned responsibility; we learned to help each other. I don’t envy the kids here [in US] at all. I wouldn’t have traded it for the world.”

Eva’s life is as ordinary as it is extraordinary. She pulls out her dusty photo albums, and from the yellowed pages peers out a vivacious young woman, drinking at a bar with friends, perched on the wing-tip of a B-29 bomber, giggling on the arm of a New Mexico sweetheart in an American army uniform. Her smile, her demeanor, her utter vibrancy belied what she was suffering.

When I first met her at a conference at the Ner Shalom synagogue in Cotati, California, these were the things that defined Eva the most. I have read many books on the Holocaust, heard many speakers, and watched many videos. But Eva was the first survivor I interviewed. And despite her denial, she is a survivor. I left with a strong conviction that personal communication is far more powerful than anything that the media can produce. Communication is what we, as students, can instigate to ensure that the Holocaust is indeed, “never again”.

I will forever carry in my heart the image of a little girl in a cold, bare Italian train station, not knowing whether she would be allowed to leave and live. These are the images that remind us that we live in a world ridden with prejudice, hatred, and violence. Thus it is our responsibility, that we not only say, “we remember” but live by that phrase every day. In remembering those who were victims of prejudice and discrimination, we must learn to relinquish the weapons of prejudice and hatred ourselves.

Sometimes it seems near impossible.

Then I asked Eva whether she or Jews of Shanghai ever thought of vengeance. She shook her head furiously: “There was sadness. There was sorrow. There always will be sorrow. But revenge - no, no, never.”

This statement will never cease to inspire me.

免责声明:本文中使用的图片均由博主自行发布,与本网无关,如有侵权,请联系博主进行删除。

全部作者的其他最新博文

发表评论 评论 (61 个评论)

- 回复 AUTUMN_TREE

- 谈到历史总是很沉重

- 回复 白露为霜

- 谢谢留言。有些人喜欢强调犹太人怎样招人恨,但这都不能成为把600万犹太人送进焚化炉的借口。

杭州的欸乃山水: 就人物本身经历的内容言,故事的描述、结构已相当不错。语言很干净,不知该归功于原文还是翻译。对犹太人迫害与大屠杀的记忆是人类宝贵的精神财富。对犹太历史文 ...

- 回复 zjwang8888

- good luck.

- 回复 杭州的欸乃山水

- 就人物本身经历的内容言,故事的描述、结构已相当不错。语言很干净,不知该归功于原文还是翻译。对犹太人迫害与大屠杀的记忆是人类宝贵的精神财富。对犹太历史文化的讨论是正常的,但应避免模糊、否认人类精神价值建构所依赖的基本事实。

- 回复 白露为霜

- 谢谢留言。

Yougege: The farther backward you can look, the farther forward you will see and thanks your great sharing up...

- 回复 Yougege

- The farther backward you can look, the farther forward you will see and thanks your great sharing up...

- 回复 ludi

- 公平地说,我也只是从资料里看到一些记载。如果大宝有机会深入的话,可以跟伊娃交谈。先去掉“幸存者”这个假设。了解一下当时犹太人在中国和日本的全貌。

或许我们可以更理智地看待历史,学到更多的知识。

- 回复 ludi

- 我倒不是在说犹太人比中国人过得好还是差。

白露为霜: 那时候,中国人和犹太人是难兄难弟。刚开始时日本人未占据租界,犹太人还算好过。珍珠港以后,日本占领租界,那些英美法籍的犹太人都给关了起来,包括沙逊这样的 ...

我的Point 是在中国的犹太人与在欧洲的犹太人不是一回事。

犹太人到中国被日本人当作客人对待。日本神户,就有大批从俄国来的犹太人,蜂拥而至多到让日本政府感到无法承受的地步。

只有一批2万人后来左右从奥地利和德国来的犹太难民,在德国的强力要求下,日本把他们集中在上海隔离区。那些人比较苦一些。但是日本占领军拒绝了德国处决难民的要求。只是不准随便离开隔离区。德国人本来是要设法处死那些难民的。那是犹太人相当与是德国来的“逃犯”。

如果说Oskar Schindler 是德国犹太人的救命恩人,那么日本人同样也“救了”那批犹太人。这么说应该不过分。

犹太人在中国/日本的处境与他们在德国集中营的遭遇完全不是一码事。整体来说,犹太人不仅没有受到日本人虐待,而且还享受外国人的礼遇。相反,在日本的铁蹄下中国人是被虐待的民族。

- 回复 白露为霜

- 那时候,中国人和犹太人是难兄难弟。刚开始时日本人未占据租界,犹太人还算好过。珍珠港以后,日本占领租界,那些英美法籍的犹太人都给关了起来,包括沙逊这样的富豪,无国籍犹太人被隔离。讨论中国人和犹太人在日本占领下那一个过得好并没有意义。

ludi: 哈,是我误解了。

对于上海那一段的历史,其实有两种犹太人。一种是在中国已经发了财的犹太人,一种是被纳粹和苏俄驱赶出来流离失所的犹太人。

相比与中国人, ...

- 回复 ludi

- 哈,是我误解了。

白露为霜: 这不是我的意思。我是说上海犹太人这段历史即是中国人历史也是犹太人的历史。在这个时间和地点有交集。

对于上海那一段的历史,其实有两种犹太人。一种是在中国已经发了财的犹太人,一种是被纳粹和苏俄驱赶出来流离失所的犹太人。

相比与中国人,如果我们深入地分析那时的心态,犹太人到了上海是等于是逃离了水深火热,不再亡命天涯。日本人欢迎犹太人。而中国人,却是在铁蹄之下的被征服者,是奴隶。

- 回复 白露为霜

- 这不是我的意思。我是说上海犹太人这段历史即是中国人历史也是犹太人的历史。在这个时间和地点有交集。

ludi: 我不同意中国人和犹太人有相同历史的的观点。

中国人有自己的国土。中国从中原起家,打下一片领土,占据半壁河山。

犹太人是个流浪的民族。他们像是蝴蝶和毛毛 ...

- 回复 ludi

- 我不同意中国人和犹太人有相同历史的的观点。

白露为霜: 犹太人可爱不可爱并不重要。这是一段中国人同犹太人共有的历史,再加上日本人,关系相当复杂。是历史就应该加以适当地研究。 ...

中国人有自己的国土。中国从中原起家,打下一片领土,占据半壁河山。

犹太人是个流浪的民族。他们像是蝴蝶和毛毛虫,飘哪里吃那里。掏空别人,肥了自己。

- 回复 白露为霜

- 犹太人可爱不可爱并不重要。这是一段中国人同犹太人共有的历史,再加上日本人,关系相当复杂。是历史就应该加以适当地研究。

ludi: Fugu Plot 本身是否是个定论不是问题的关键。关键的是犹太人对中国人来说不可爱。

- 回复 ludi

- Fugu Plot 本身是否是个定论不是问题的关键。关键的是犹太人对中国人来说不可爱。

白露为霜: 并不是定论。

Despite there being little evidence to suggest that the Japanese had ever contemplated a Jewish state or a Jewish autonomous region,[6] ...

- 回复 白露为霜

- 并不是定论。

ludi: 那么白露就欠我一个人情了哈

它叫做: Fugu Plot (河豚計画 Fugu keikaku?)

Wiki里面就有:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proposals_for_a_Jewish_sta ...

Despite there being little evidence to suggest that the Japanese had ever contemplated a Jewish state or a Jewish autonomous region,[6] Rabbi Marvin Tokayer and Mary Swartz published a book called 'The Fugu Plan' in 1979. In this partly fictionalized book, Tokayer & Swartz gave the name the Fugu Plan or Fugu Plot (河豚計画, Fugu keikaku?) to memorandums written in the 1930s Imperial Japan proposing settling Jewish refugees escaping Nazi-occupied Europe in Japanese territories. Tokayer and Swartz claim that the plan, which was viewed by its proponents as risky but potentially rewarding for Japan, was named after the Japanese word for puffer-fish, a delicacy which can be fatally poisonous if incorrectly prepared.[7]

Tokayer and Swartz base their claim on statements made by Captain Koreshige Inuzuka. They alleged that such a plan was first discussed in 1934 and then solidified in 1938, supported by notables such as Inuzuka, Ishiguro Shiro and Norihiro Yasue;[8] however, the signing of the Tripartite Pact in 1941 and other events prevented its full implementation. The memorandums were not called The Fugu Plan.

Ben-Ami Shillony, a professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, confirms that the statements upon which Tokayer and Swartz based their claim were taken out of context, and that the translation with which they worked was flawed. Shillony's view is further supported by Kiyoko Inuzuka .[9] In 'The Jews and the Japanese: The Successful Outsiders', he questioned whether the Japanese ever contemplated establishing a Jewish state or a Jewish autonomous region